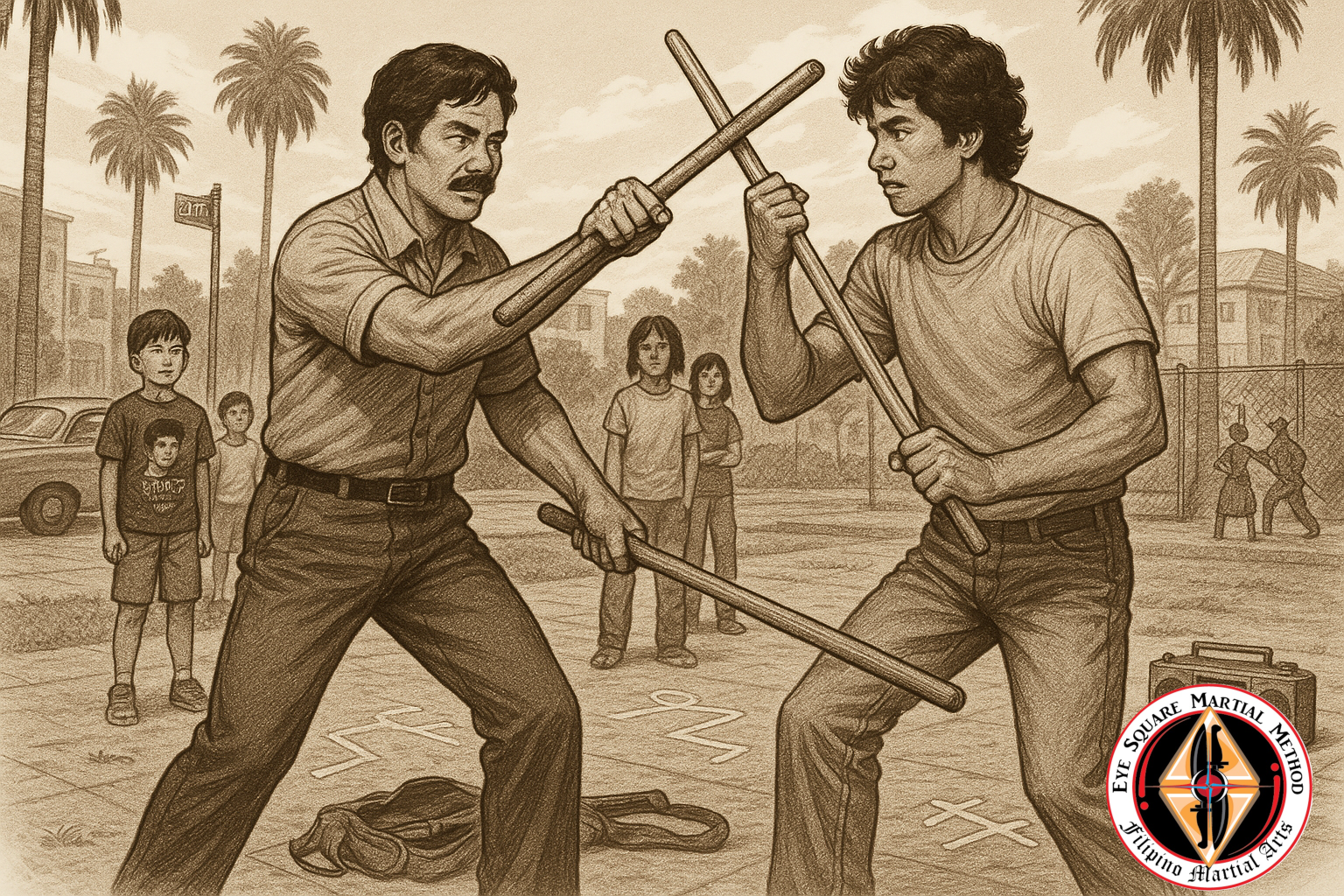

If you’ve ever been cracked on the knuckles during a sinawali drill and thought, “There’s gotta be a story behind all this,” you’re absolutely right.

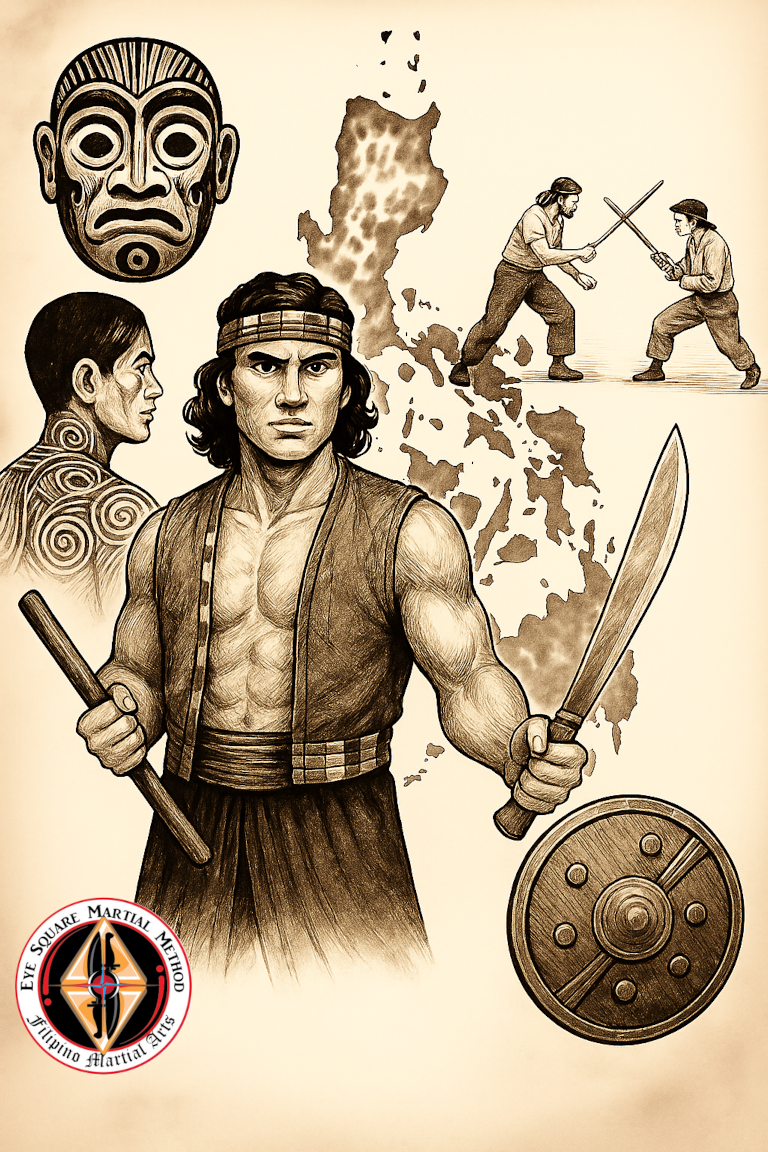

Filipino Martial Arts—Arnis, Eskrima, Kali—are more than just sticks and strikes. They’re deeply rooted in the history, culture, and resistance of the Philippine islands. Whether you’re new to the arts or have been swinging a baston for years, understanding where it all comes from adds depth to every movement.

Here’s a handpicked, annotated list of books and films to deepen your knowledge of FMA and the cultural forces that shaped it.

🗡️ Historical and Cultural Foundations

1. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society – William Henry Scott

A must-read for precolonial Filipino life. It covers warfare, social classes, and how early communities functioned. Great for understanding the roots of indigenous martial traditions.

2. Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino – William Henry Scott

Debunks colonial myths and gives voice to what pre-Spanish Filipino life may have really looked like. Think of it as the historical groundwork beneath your footwork.

3. An Anarchy of Families – Edited by Alfred W. McCoy

Less about martial arts directly, but packed with insight on how power, violence, and family dynasties shaped Filipino society. It gives context to how martial skills were preserved and used.

🏋️️ Martial Arts-Specific Studies

4. The Filipino Martial Arts – Dan Inosanto

The book that opened Western eyes to FMA. A solid intro with history, technique, and personal stories. If you train, you should own this.

5. Filipino Martial Culture – Mark V. Wiley

Part cultural anthropology, part martial arts tour. Interviews, system overviews, and an honest look at how the arts have evolved.

6. The History of Filipino Martial Arts – Felipe P. Jocano Jr.

An academic and practitioner’s view. This one digs into the historical transitions FMA went through—from tribal warfare to colonial resistance.

🌍 FMA in the Modern World

7. Kali’s Odyssey – Christopher Ricketts (interviews)

A look at how FMA traveled with the Filipino diaspora, especially into the U.S. You’ll get a feel for how the art continues to evolve abroad.

8. RA 9850 (2009): The Arnis Law

Not a book, but an official recognition by the Philippine government naming Arnis the national martial art and sport. A big deal for preservation and legitimacy.

🎥 Documentaries and Oral Histories

9. Eskrimadors (2010, Dir. Kerwin Go)

A well-produced doc on Cebu-based masters and their systems. Solid footage and interviews. If you want to see FMA in action, start here.

10. The Bladed Hand (2012, Dir. Jay Ignacio)

Explores the global reach of FMA with interviews from masters around the world. Shows how the art thrives far beyond the islands.

Final Thoughts

You can swing a stick without knowing the history. But once you do know the history? Every strike hits different.

Whether you’re building your bookshelf or your footwork, these resources will help you connect the dots between the blade, the hand, and the culture that shaped them both.