After surviving centuries of colonization and a world war, Filipino Martial Arts emerged from the smoke not just intact—but ready to travel. The second half of the 20th century marked the beginning of FMA’s transformation from a secret kept in backyards and barrios to a respected, global martial system. And it all started with one simple truth: people started talking.

Veterans Started Teaching

After WWII, many of the men who had fought in the jungles came home and began organizing what they had learned. Some were already informal teachers. But now, systems began to form. Drills were refined. Techniques were cataloged. And for the first time, many of these arts got names—Modern Arnis, Doce Pares, Balintawak, Pekiti-Tirsia, and more.

Martial arts schools popped up in the Philippines, often still taught behind homes, in church courtyards, or anywhere with enough space to swing a stick. Rank systems were introduced. Uniforms were optional, but pride was not.

The Diaspora Effect

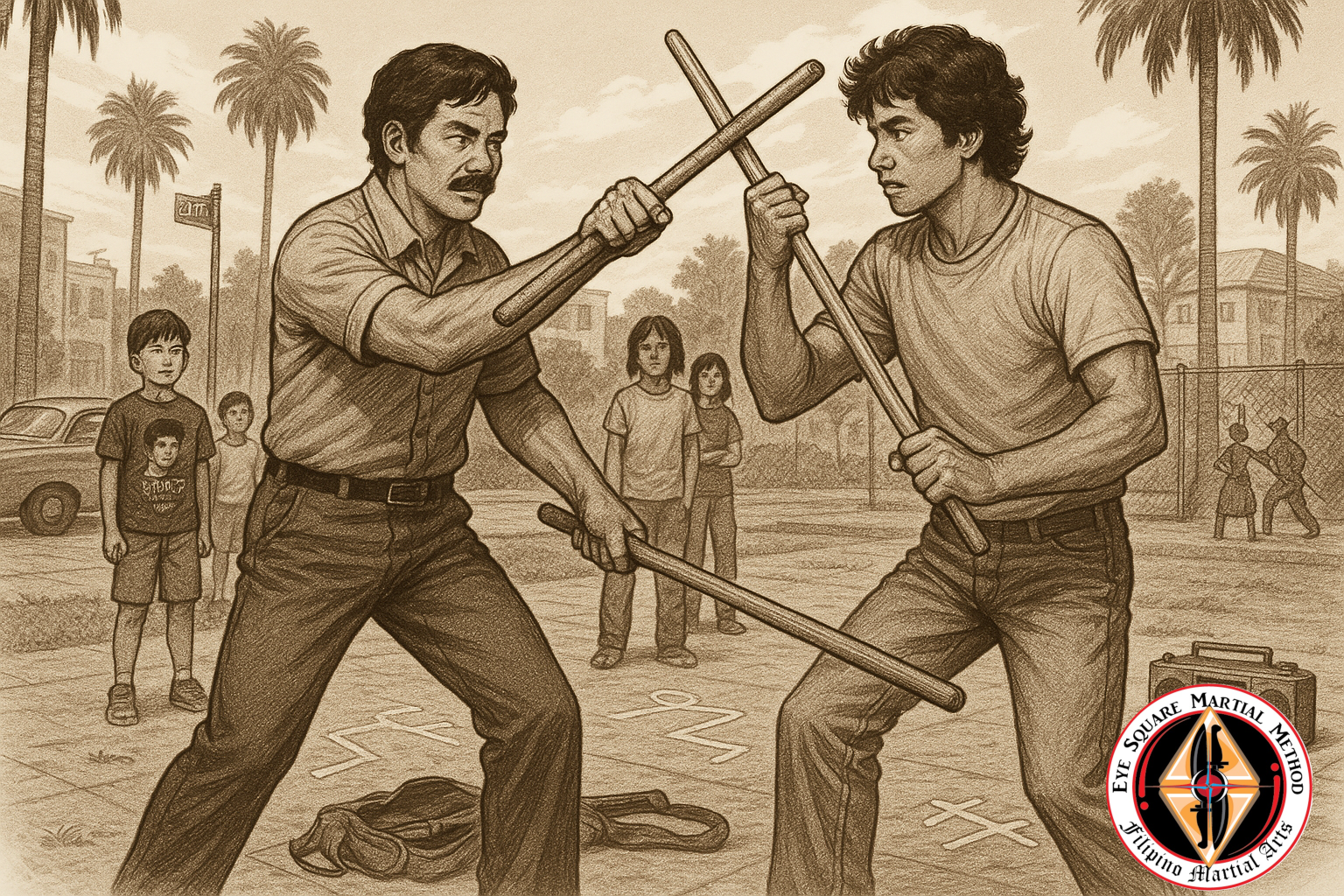

As Filipinos migrated abroad—to the U.S., Canada, Australia, Europe—they took their culture with them. And that included their martial arts. What started as stick drills in garages or parks turned into full-blown schools. Filipino martial artists in California played a huge role in spreading the art—especially in places like Stockton and Los Angeles.

And then, of course, came a little boost from Hollywood.

Enter Bruce Lee (and Dan Inosanto)

When Bruce Lee started exploring martial arts beyond Wing Chun, he found himself learning from Dan Inosanto—a Filipino-American martial artist trained in FMA. Suddenly, Filipino techniques were showing up on the big screen. Knife work, stick drills, limb destructions—they all looked cool and hit hard.

This was huge. Bruce Lee gave FMA a moment on the world stage. Dan Inosanto gave it structure, visibility, and credibility. And the global martial arts community started paying attention.

From Combat to Curriculum

By the 1980s and 90s, FMA was becoming a staple in military combatives programs, law enforcement training, and civilian self-defense. The arts adapted again—this time for modern threats. Knife defense. Weapon retention. Multiple attacker scenarios. The same principles that worked against invading forces now applied to street-level survival.

Seminars became the norm. Global organizations formed. Filipino grandmasters were invited to teach internationally. What was once a village art had become a global phenomenon.

The Cultural Tradeoff

Of course, with growth comes change. Some systems leaned into sport formats. Others clung fiercely to tradition. Still others got sliced and diced into weekend workshops with little cultural context. But through it all, one thing remained: the arts still worked.

They remained brutal, efficient, adaptable—and unapologetically Filipino.

In the next chapter, we’ll bring things up to the present and explore how Arnis, Eskrima, and Kali are being preserved, promoted, and practiced today—and what it means to be a modern-day practitioner of these warrior arts.