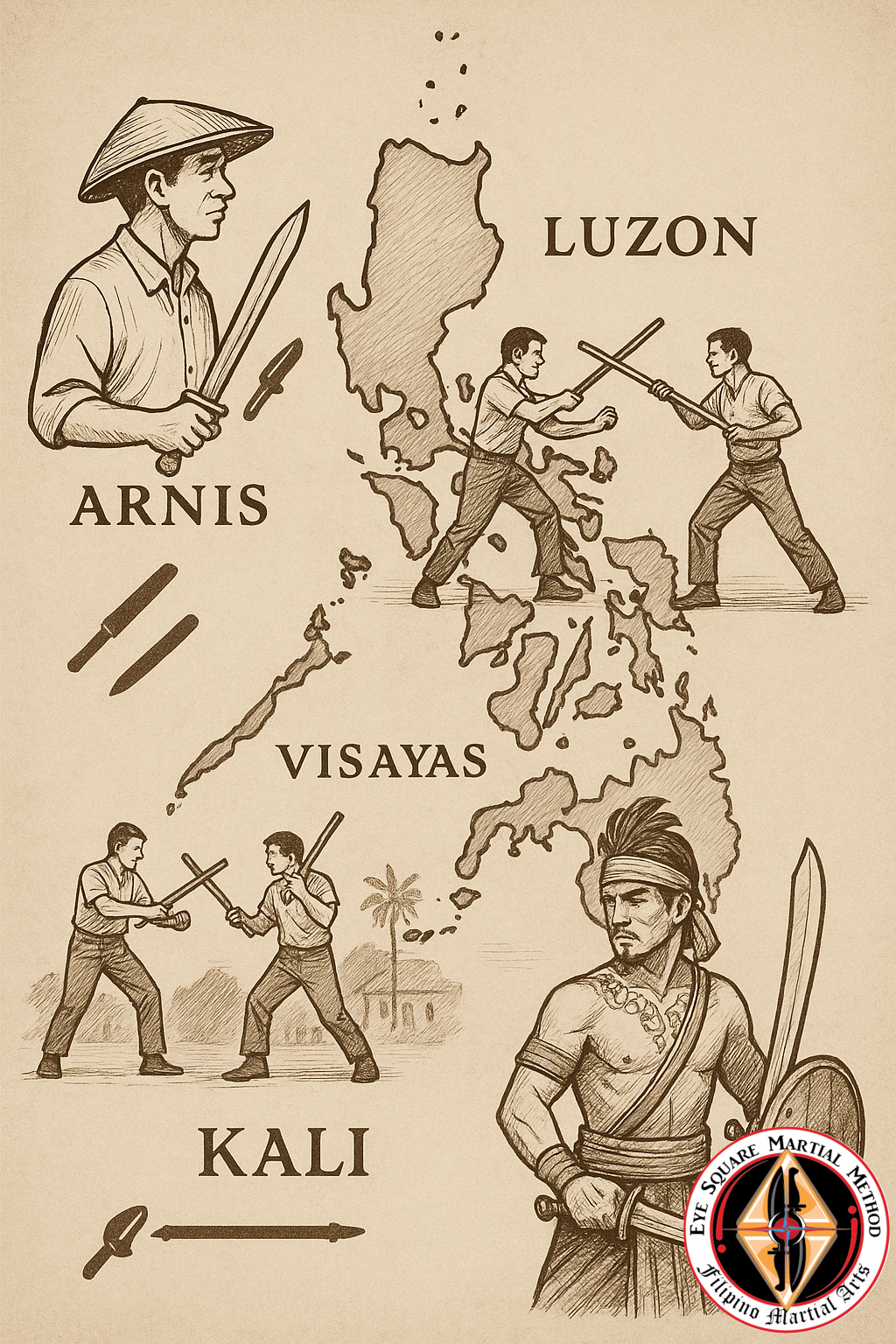

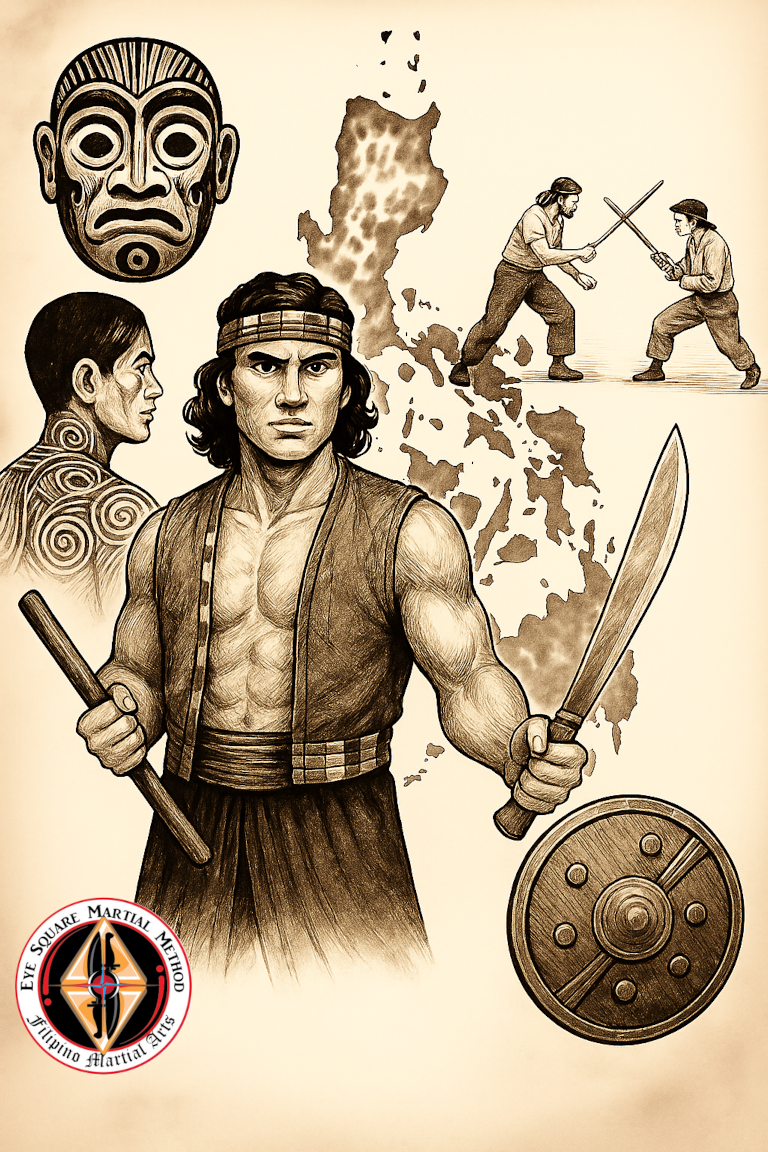

Filipino Martial Arts aren’t a single unified system—they’re a constellation of styles, strategies, and traditions, shaped by the geography, culture, and history of the islands they come from. Each region brought something to the table, and understanding those roots helps us appreciate just how diverse and adaptable FMA really is.

Luzon – Arnis and Blade Discipline

In the northern islands, especially in central and northern Luzon, the term Arnis de Mano became dominant. While there are stick systems, blade work has always been a big deal here—particularly with bolos, talibongs, and other agricultural tools-turned-weapons. Systems here often emphasize:

- Flow drills (Anyo or Sayaw)

- Blade-first mentality

- Integration with cultural dances and traditions

- Strong Spanish-era fencing influence

Notable provinces: Pangasinan, Ilocos, Nueva Ecija, and parts of Central Luzon.

Visayas – Eskrima and Impact Power

The Visayas are the heartland of Eskrima (or Esgrima, derived from Spanish fencing). In Cebu, Negros, Iloilo, and nearby islands, you’ll find some of the most systematized and well-known FMA styles. Eskrima in this region is known for:

- Close-range stick fighting

- Fast, aggressive striking

- Conceptual flow (defanging the snake, zoning)

- Family-based systems passed down generation to generation

Notable systems: Balintawak, Doce Pares, Cacoy Doce Pares, and others that trace their roots to Cebu.

Mindanao – Kali and Tribal Warrior Influence

While the term Kali is debated and varies by usage, it’s often associated with Mindanao and the southern Philippines. These regions have long histories of resistance and warrior traditions among the Moro people and indigenous tribes. Kali here carries:

- Blade-centric training (kris, kampilan, barong)

- Influence from Islamic and tribal warrior culture

- Integrated weapons systems (sword, shield, spear)

- Tactics suited for actual tribal warfare and skirmish combat

Notable areas: Sulu, Cotabato, Lanao del Sur, Zamboanga, Maguindanao

Tagalog and Bicol Regions – Hybrids and Hidden Arts

In the southern Luzon regions (Tagalog belt and Bicol), FMA systems often flew under the radar. These arts were passed down through families, embedded in ritual and custom. They may not have always had formal names, but they were battle-tested and efficient.

- Bolos and machete work

- Stick and knife integration

- Farm tool adaptability

- Often blended with local dance or religious festivities for concealment

Why Regional Origins Matter

Knowing where an art comes from helps you understand why it looks the way it does. Terrain, local weapons, colonial contact, and even climate shaped how people fought. A system from the highlands of Luzon looks different than one from the flatlands of Cebu—or the jungle regions of Mindanao.

The magic of FMA is that it all works together. Each system reflects its environment, but the principles—movement, timing, adaptability—are universal.

So whether you call it Arnis, Eskrima, Kali, or something else entirely, know this: you’re tapping into centuries of innovation, rooted in the land, the people, and the fight to survive.